Before we start considering classes in C#, which implement some of the most frequently, used data structures (such as lists and queues), we are going to consider the concepts of data structures and abstract data structures.

What Is a Data Structure?

Very often, when we write programs, we have to work with many objects (data). Sometimes we add and remove elements, other times we would like to order them or to process the data in another specific way. For this reason, different ways of storing data are developed, depending on the task. Most frequently these elements are ordered in some way (for example, object A is before object B).

At this point we come to the aid of data structures – a set of data organized on the basis of logical and mathematical laws. Very often the choice of the right data structure makes the program much more efficient – we could save memory and execution time (and sometimes even the amount of code we write).

What Is an Abstract Data Type?

In general, abstract data types (ADT) gives us a definition (abstraction) of the specific structure, i.e. defines the allowed operations and properties, without being interested in the specific implementation. This allows an abstract data type to have several different implementations and respectively different efficiency.

Basic Data Structures in Programming

We can differentiate several groups of data structures:

– Linear – these include lists, stacks and queues

– Tree-like – different types of trees like binary trees, B-trees and balanced trees

– Dictionaries – key-value pairs organized in hash tables

– Sets – unordered bunches of unique elements

– Others – multi-sets, bags, multi-bags, priority queues, graphs, …

In this chapter we are going to explore the linear (list-like) data structures, and in the next several chapters we are going to pay attention to more complicated data structures, such as trees, graphs, hash tables and sets, and we are going to explain how and when to use each of them.

Mastering basic data structures in programming is essential, as without them we could not program efficiently. They, together with algorithms, are in the basis of programming and in the next several chapters we are going to get familiar with them.

Most commonly used data structures are the linear (list) data structures. They are an abstraction of all kinds of rows, sequences, series and others from the real world.

List

We could imagine the list as an ordered sequence (line) of elements. Let’s take as an example purchases from a shop. In the list we can read each of the elements (the purchases), as well as add new purchases in it. We can also remove (erase) purchases or shuffle them.

Abstract Data Structure “List”

Let’s now give a more strict definition of the structure list:

List is a linear data structure, which contains a sequence of elements. The list has the property length (count of elements) and its elements are arranged consecutively.

The list allows adding elements on different positions, removing them and incremental crawling. Like we already mentioned, an ADT can have several implementations. An example of such ADT is the interface System.

Collections.IList.

Interfaces in C# construct a frame (contract) for their implementations – classes. This contract consists of a set of methods and properties, which each class must implement in order to implement the interface. The data type “Interface” in C# we are going to discuss in depth in the chapter “Object-Oriented Programming Principles”.

Each ADT defines some interface. Let’s consider the interface System.

Collections.IList. The basic methods, which it defines, are:

– int Add(object) – adds element in the end of the list

– void Insert(int, object) – adds element on a preliminary chosen position in the list

– void Clear() – removes all elements in the list

– bool Contains(object) – checks whether the list contains the element

– void Remove(object) – removes the element from the list

– void RemoveAt(int) – removes the element on a given position

– int IndexOf(object) – returns the position of the element

– this[int] – indexer, allows access to the elements on a set position

Let’s see several from the basic implementations of the ADT list and explain in which situations they should be used.

Static List (Array-Based Implementation)

Arrays perform many of the features of the ADT list, but there is a significant difference – the lists allow adding new elements, while arrays have fixed size.

Despite of that, an implementation of list is possible with an array, which automatically increments its size (similar to the class StringBuilder, which we already know from the chapter “Strings”). Such list is called static list implemented with an extensible array. Below we shall give a sample implementation of auto-resizable array-based list (array list). It is intended to hold any data type T through the concept of generics (see the “Generics” section in chapter “Defining Classes”):

| public class CustomArrayList<T>{ private T[] arr; private int count; /// <summary>Returns the actual list length</summary> public int Count { get { return this.count; } } private const int INITIAL_CAPACITY = 4; /// <summary> /// Initializes the array-based list – allocate memory /// </summary> public CustomArrayList(int capacity = INITIAL_CAPACITY) { this.arr = new T[capacity]; this.count = 0; } |

Firstly, we define an array, in which we are going to keep the elements, as well as a counter for the current count of elements. After that we add the constructor, as we initialize our array with some initial capacity (when capacity is not specified) in order to avoid resizing it when adding the first few elements. Let’s take a look at some typical operations like add (append) an element, insert an element at specified position (index) and clear the list:

| /// <summary>Adds element to the list</summary>/// <param name=”item”>The element you want to add</param>public void Add(T item){ GrowIfArrIsFull(); this.arr[this.count] = item; this.count++;} /// <summary>/// Inserts the specified element at given position in this list/// </summary>/// <param name=”index”>/// Index, at which the specified element is to be inserted/// </param>/// <param name=”item”>Element to be inserted</param>/// <exception cref=”System.IndexOutOfRangeException”>Index is invalid</exception>public void Insert(int index, T item){ if (index > this.count || index < 0) { throw new IndexOutOfRangeException( “Invalid index: ” + index); } GrowIfArrIsFull(); Array.Copy(this.arr, index, this.arr, index + 1, this.count – index); this.arr[index] = item; this.count++;} /// <summary>/// Doubles the size of this.arr (grow) if it is full/// </summary>private void GrowIfArrIsFull(){ if (this.count + 1 > this.arr.Length) { T[] extendedArr = new T[this.arr.Length * 2]; Array.Copy(this.arr, extendedArr, this.count); this.arr = extendedArr; }} /// <summary>Clears the list (remove everything)</summary>public void Clear(){ this.arr = new T[INITIAL_CAPACITY]; this.count = 0;} |

We implemented the operation adding a new element, as well as inserting a new element which both first ensure that the internal array (buffer) holding the elements has enough capacity. If the internal buffer is full, it is extended (grown) to a double of the current capacity. Since arrays in .NET do not support resizing, the growing operation allocated a new array of double size and moves all elements from the old array to the new.

Below we implement searching operations (finding the index of given element and checking whether given element exists), as well as indexer – the ability to access the elements (for read and change) by their index specified in the [] operator:

| /// <summary>/// Returns the index of the first occurrence of the specified/// element in this list (or -1 if it does not exist)./// </summary>/// <param name=”item”>The element you are searching</param>/// <returns>/// The index of a given element or -1 if it is not found/// </returns>public int IndexOf(T item){ for (int i = 0; i < this.arr.Length; i++) { if (object.Equals(item, this.arr[i])) { return i; } } return -1;} /// <summary>Checks if an element exists</summary>/// <param name=”item”>The item to be checked</param>/// <returns>If the item exists</returns>public bool Contains(T item){ int index = IndexOf(item); bool found = (index != -1); return found;} /// <summary>Indexer: access to element at given index</summary>/// <param name=”index”>Index of the element</param>/// <returns>The element at the specified position</returns>public T this[int index]{ get { if (index >= this.count || index < 0) { throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException( “Invalid index: ” + index); } return this.arr[index]; } set { if (index >= this.count || index < 0) { throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException( “Invalid index: ” + index); } this.arr[index] = value; }} |

We add operations for removing items (by index and by value):

| /// <summary>Removes the element at the specified index/// </summary>/// <param name=”index”>The index of the element to remove/// </param>/// <returns>The removed element</returns>public T RemoveAt(int index){ if (index >= this.count || index < 0) { throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException( “Invalid index: ” + index); } T item = this.arr[index]; Array.Copy(this.arr, index + 1, this.arr, index, this.count – index – 1); this.arr[this.count – 1] = default(T); this.count–; return item;} /// <summary>Removes the specified item</summary>/// <param name=”item”>The item to be removed</param>/// <returns>The removed item’s index or -1 if the item does not exist</returns>public int Remove(T item){ int index = IndexOf(item); if (index != -1) { this.RemoveAt(index); } return index;} |

In the methods above we remove elements. For this purpose, firstly we find the searched element, remove it and then shift the elements after it by one position to the left, in order to fill the empty position. Finally, we fill the position after the last item in the array with null value (the default(T)) to allow the garbage collector to release it if it is not needed. Generally, we want to keep all unused elements in the arr empty (null / zero value).

Let’s consider a sample usage of the recently implemented class. There is a Main() method, in which we demonstrate most of the operations. In the enclosed code we create a list of purchases, add, insert and remove few items and print the list on the console. Finally we check whether certain items exist:

| class CustomArrayListTest{ static void Main() { CustomArrayList<string> shoppingList = new CustomArrayList<string>(); shoppingList.Add(“Milk”); shoppingList.Add(“Honey”); shoppingList.Add(“Olives”); shoppingList.Add(“Water”); shoppingList.Add(“Beer”); shoppingList.Remove(“Olives”); shoppingList.Insert(1, “Fruits”); shoppingList.Insert(0, “Cheese”); shoppingList.Insert(6, “Vegetables”); shoppingList.RemoveAt(0); shoppingList[3] = “A lot of ” + shoppingList[3]; Console.WriteLine(“We need to buy:”); for (int i = 0; i < shoppingList.Count; i++) { Console.WriteLine(” – ” + shoppingList[i]); } Console.WriteLine(“Position of ‘Beer’ = {0}”, shoppingList.IndexOf(“Beer”)); Console.WriteLine(“Position of ‘Water’ = {0}”, shoppingList.IndexOf(“Water”)); Console.WriteLine(“Do we have to buy Bread? ” + shoppingList.Contains(“Bread”)); }} |

Here is how the output of the program execution looks like:

| We need to buy: – Milk – Fruits – Honey – A lot of Water – Beer – VegetablesPosition of ‘Beer’ = 4Position of ‘Water’ = -1Do we have to buy Bread? False |

Linked List (Dynamic Implementation)

As we saw, the static list has a serious disadvantage – the operations for inserting and removing items from the inside of the array requires rearrangement of the elements. When frequently inserting and removing items (especially a large number of items), this can lead to low performance. In such cases it is advisable to use the so called linked lists. The difference in them is the structure of elements – while in the static list the element contains only the specific object, with the dynamic list the elements keep information about their next element.

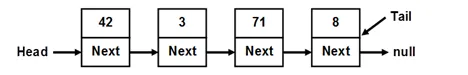

Here is how a sample linked list looks like in the memorFor the dynamic implementation of the linked list we will need two classes: the class ListNode, which will hold a single element of the list along with its next element, and the main list class DynamicList<T> which will hold a sequence of elements as well as the head and the tail of the list:

| /// <summary>Dynamic (linked) list class definition</summary>public class DynamicList<T>{ private class ListNode { public T Element { get; set; } public ListNode NextNode { get; set; } public ListNode(T element) { this.Element = element; NextNode = null; } public ListNode(T element, ListNode prevNode) { this.Element = element; prevNode.NextNode = this; } } private ListNode head; private ListNode tail; private int count; // …} |

First, let’s consider the recursive class ListNode. It holds a single element and a reference (pointer) to the next element which is of the same class ListNode. So ListNode is an example of recursive data structure that is defined by referencing itself. The class is inner to the class DynamicList<T> (it is declared as a private member) and is therefore accessible only to it. For our DynamicList<T> we create 3 fields: head – pointer to the first element, tail – pointer to the last element and count – counter of the elements.

After that we declare the constructor which creates and empty linked list:

| public DynamicList(){ this.head = null; this.tail = null; this.count = 0;} |

Upon the initial construction the list is empty and for this reason we assign head = tail = null and count = 0.

We are going to implement all basic operations: adding and removing items, as well as searching for an element and accessing the elements by index.

Let’s start with the operation add (append) which is relatively simple. Two cases are considered: an empty list and a non-empty list. In both cases we append the element at the end of the list (where tail points) and after the operation all fields (head, tail and count) have correct values:

| /// <summary>Add element at the end of the list</summary>/// <param name=”item”>The element to be added</param>public void Add(T item){ if (this.head == null) { // We have an empty list -> create a new head and tail this.head = new ListNode(item); this.tail = this.head; } else { // We have a non-empty list -> append the item after tail ListNode newNode = new ListNode(item, this.tail); this.tail = newNode; } this.count++;} |

You can now see the operation removing an item at specified index. It is considerably more complicated than adding:

| /// <summary>Removes and returns element on the specified index/// </summary>/// <param name=”index”>The index of the element to be removed/// </param>/// <returns>The removed element</returns>/// <exception cref=”System.ArgumentOutOfRangeException”>/// if the index is invalid</exception>public T RemoveAt(int index){ if (index >= count || index < 0) { throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException( “Invalid index: ” + index); } // Find the element at the specified index int currentIndex = 0; ListNode currentNode = this.head; ListNode prevNode = null; while (currentIndex < index) { prevNode = currentNode; currentNode = currentNode.NextNode; currentIndex++; } // Remove the found element from the list of nodes RemoveListNode(currentNode, prevNode); // Return the removed element return currentNode.Element;} /// <summary>/// Remove the specified node from the list of nodes/// </summary>/// <param name=”node”>the node for removal</param>/// <param name=”prevNode”>the predecessor of node</param>private void RemoveListNode(ListNode node, ListNode prevNode){ count–; if (count == 0) { // The list becomes empty -> remove head and tail this.head = null; this.tail = null; } else if (prevNode == null) { // The head node was removed –> update the head this.head = node.NextNode; } else { // Redirect the pointers to skip the removed node prevNode.NextNode = node.NextNode; } // Fix the tail in case it was removed if (object.ReferenceEquals(this.tail, node)) { this.tail = prevNode; }} |

Firstly, we check if the specified index exists, and if it does not, an appropriate exception is thrown. After that, the element for removal is found by moving forward from the beginning of the list to the next element exactly index times. After the element for removal has been found (currentNode), it is removed by the additional private method RemoveListNode(…), which considers the following 3 possible cases:

– The list remains empty after the removal à we remove the whole list along with its head and tail (head = null, tail = null, count = 0).

– The element for removal is at the start of the list (there is no previous element) à we make head to point at the element immediately after the removed element (or at null, if the removed element was the last one).

– The element is in the middle or at the end of the list à we direct the element before it to point to the element after it (or at null, if there is no next element).

Finally, we make sure tail points to the end of the list (in case tail was pointed to the removed element, it is fixed to point to its predecessor).

The next is the implementation of the removal of an element by its value:

| /// <summary>/// Removes the specified item and return its index./// </summary>/// <param name=”item”>The item for removal</param>/// <returns>The index of the element or -1 if it does not exist</returns>public int Remove(T item){ // Find the element containing the searched item int currentIndex = 0; ListNode currentNode = this.head; ListNode prevNode = null; while (currentNode != null) { if (object.Equals(currentNode.Element, item)) { break; } prevNode = currentNode; currentNode = currentNode.NextNode; currentIndex++; } if (currentNode != null) { // The element is found in the list -> remove it RemoveListNode(currentNode, prevNode); return currentIndex; } else { // The element is not found in the list -> return -1 return -1; }} |

The removal by value of an element works like the removal of an element by index, but there are two special considerations: the searched element may not exist and for this reason an extra check is necessary; there may be elements with null value in the list, which have to be removed and processed correctly. The last is done by comparing the elements through the static method object.Equals(…) which works well with null values.

In order the removal to work correctly, it is necessary the elements in the array to be comparable, i.e. to have a correct implementation of the method Equals() derived from System.Object.

Bellow we give implementations of the operations for searching and checking whether the list contains a specified element:

| /// <summary>Searches for given element in the list</summary>/// <param name=”item”>The item to be searched</param>/// <returns>/// The index of the first occurrence of the element/// in the list or -1 when it is not found/// </returns>public int IndexOf(T item){ int index = 0; ListNode currentNode = this.head; while (currentNode != null) { if (object.Equals(currentNode.Element, item)) { return index; } currentNode = currentNode.NextNode; index++; } return -1;} /// <summary>/// Checks if the specified element exists in the list/// </summary>/// <param name=”item”>The item to be checked</param>/// <returns>/// True if the element exists or false otherwise/// </returns>public bool Contains(T item){ int index = IndexOf(item); bool found = (index != -1); return found;} |

The searching for an element works like in the method for removing: we start from the beginning of the list and check sequentially the next elements one after another, until we reach the end of the list or find the searched element.

We have two more operations to implement – accessing elements by index (using the indexer) and finding the count of elements (through a property):

| /// <summary>/// Gets or sets the element at the specified position/// </summary>/// <param name=”index”>/// The position of the element [0 … count-1]/// </param>/// <returns>The item at the specified index</returns>/// <exception cref=”System.ArgumentOutOfRangeException”>/// When an invalid index is specified/// </exception>public T this[int index]{ get { if (index >= count || index < 0) { throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException( “Invalid index: ” + index); } ListNode currentNode = this.head; for (int i = 0; i < index; i++) { currentNode = currentNode.NextNode; } return currentNode.Element; } set { if (index >= count || index < 0) { throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException( “Invalid index: ” + index); } ListNode currentNode = this.head; for (int i = 0; i < index; i++) { currentNode = currentNode.NextNode; } currentNode.Element = value; }} /// <summary>/// Gets the count of elements in the list/// </summary>public int Count{ get { return this.count; }} |

The indexer works pretty straightforward – first checks the validity of the specified index and then starts from the head of the list goes to the next node index times. Once the node containing the element the specified index is found, it is accessed directly.

Let’s finally see a shopping list example similar to the example with the static list implementation, this time using with our linked list:

| class DynamicListTest{ static void Main() { DynamicList<string> shoppingList = new DynamicList<string>(); shoppingList.Add(“Milk”); shoppingList.Remove(“Milk”); // Empty list shoppingList.Add(“Honey”); shoppingList.Add(“Olives”); shoppingList.Add(“Water”); shoppingList[2] = “A lot of ” + shoppingList[2]; shoppingList.Add(“Fruits”); shoppingList.RemoveAt(0); // Removes “Honey” (first) shoppingList.RemoveAt(2); // Removes “Fruits” (last) shoppingList.Add(null); shoppingList.Add(“Beer”); shoppingList.Remove(null); Console.WriteLine(“We need to buy:”); for (int i = 0; i < shoppingList.Count; i++) { Console.WriteLine(” – ” + shoppingList[i]); } Console.WriteLine(“Position of ‘Beer’ = {0}”, shoppingList.IndexOf(“Beer”)); Console.WriteLine(“Position of ‘Water’ = {0}”, shoppingList.IndexOf(“Water”)); Console.WriteLine(“Do we have to buy Bread? ” + shoppingList.Contains(“Bread”)); }} |

The above code checks all the operations from our linked list implementation along with their special cases (like removing the first and the last element) and shows that out dynamic list implementation works correctly. The output of the above code is the following:

| We need to buy: – Olives – A lot of Water – BeerPosition of ‘Beer’ = 2Position of ‘Water’ = -1Do we have to buy Bread? False |

Comparing the Static and the Dynamic Lists

We implemented the abstract data type (ADT) list in two ways: static (array list) and dynamic (linked list). Once written these two implementations can be used in almost exactly the same way. For example see the following two pieces of code (using our array list and our linked list):

| static void Main(){ CustomArrayList<string> arrayList = new CustomArrayList<string>(); arrayList.Add(“One”); arrayList.Add(“Two”); arrayList.Add(“Three”); arrayList[0] = “Zero”; arrayList.RemoveAt(1); Console.WriteLine(“Array list: “); for (int i = 0; i < arrayList.Count; i++) { Console.WriteLine(” – ” + arrayList[i]); } DynamicList<string> dynamicList = new DynamicList<string>(); dynamicList.Add(“One”); dynamicList.Add(“Two”); dynamicList.Add(“Three”); dynamicList[0] = “Zero”; dynamicList.RemoveAt(1); Console.WriteLine(“Dynamic list: “); for (int i = 0; i < dynamicList.Count; i++) { Console.WriteLine(” – ” + dynamicList[i]); }} |

The result of using the two types of lists is the same:

| Array list: – Zero – ThreeDynamic list: – Zero – Three |

The above example demonstrates that certain ADT could be implemented in several conceptually different ways and the users may not notice the difference between them. Still, different implementations could have different performance and could take different amount of memory.

This concept, known as abstract behavior, is fundamental for OOP and can be implemented by abstract classes or interfaces as we shall see in the section “Abstraction” of chapter “Object-Oriented Programming Principles”.

Doubly-Linked List

In the so called doubly-linked lists each element contains its value and two pointers – to the previous and to the next element (or null, if there is no such element). This allows us to traverse the list forward and backward and some operations to be implemented more efficiently. Here is how a sample doubly-linked list looks like:

The ArrayList Class

After we got familiar with some of the basic implementations of the lists, we are going to consider the classes in C#, which deliver list data structures “without lifting a finger”. The first one is the class ArrayList, which is an untyped dynamically-extendable array. It is implemented similarly to the static list implementation, which we considered earlier. ArrayList gives the opportunity to add, delete and search for elements in it. Some more important class members we may use are:

– Add(object) – adding a new element

– Insert(int, object) – adding a new element at a specified position (index)

– Count – returns the count of elements in the list

– Remove(object) – removes a specified element

– RemoveAt(int) – removes the element at a specified position

– Clear() – removes all elements from the list

– this[int] – an indexer, allows accessing the elements by a given position (index)

As we saw, one of the main problems with this implementation is the resizing of the inner array when adding and removing elements. In the ArrayList the problem is solved by preliminarily created array (buffer), which gives us the opportunity to add elements without resizing the array at each insertion or removal of elements.

The ArrayList Class – Example

The ArrayList class is untyped, so it can keep all kinds of elements – numbers, strings and other objects. Here is a small example:

| using System;using System.Collections; class ProgrArrayListExample{ static void Main() { ArrayList list = new ArrayList(); list.Add(“Hello”); list.Add(5); list.Add(3.14159); list.Add(DateTime.Now); for (int i = 0; i < list.Count; i++) { object value = list[i]; Console.WriteLine(“Index={0}; Value={1}”, i, value); } }} |

In the example we create ArrayList and we add in it several elements from different types: string, int, double and DateTime. After that we iterate over the elements and print them. If we execute the example, we are going to get the following result:

| Index=0; Value=HelloIndex=1; Value=5Index=2; Value=3.14159Index=3; Value=29.12.2009 23:17:01 |

ArrayList of Numbers – Example

In case we would like to make an array of numbers and then process them, for example to find their sum, we have to convert the object type to a number. This is because ArrayList is actually a list of elements of type object, and not from some specific type (like int or string). Here is a sample code, which sums the elements of ArrayList:

| ArrayList list = new ArrayList();list.Add(2);list.Add(3.5f);list.Add(25u);list.Add(” EUR”);dynamic sum = 0;for (int i = 0; i < list.Count; i++){ dynamic value = list[i]; sum = sum + value;}Console.WriteLine(“Sum = ” + sum);// Output: Sum = 30.5 EUR |

Note that in the array list we hold different types of values (int, float, uint and string) and we sum them in a variable of special type called dynamic. In C# dynamic is a universal data type intended to hold any value (numbers, objects, strings, even functions and methods). Operations over dynamic variables (like the + operator used above) are resolved at runtime and their action depends on the actuals values of their arguments. At compile time almost every operation with dynamic variables successfully compiles. At runtime, if the operation can be performed, it is performed, otherwise and exception is thrown. This explains why we apply the operation + over the arguments 2, 3.5f, 25u and ” EUR” and we finally obtain as a result the string “30.5 EUR”.

Generic Collections

Before we continue to play with more examples of working with the ArrayList class, we shall recall the concept of Generic Data Types in C#, which gives the opportunity to parameterize lists and collections in C#.

When we use the ArrayList class and all classes, which implement the interface System.IList, we face the problem we saw earlier: when we add a new element from a class, we pass it as a value of type object. Later, when we search for a certain element, we get it as object and we have to cast it to the expected type (or use dynamic). It is not guaranteed, however, that all elements in the list will be of one and the same type. Besides this, the conversion from one type to another takes time, and this drastically slows down the program execution.

To solve the problem we use the generic (template / parameterized) classes. They are created to work with one or several types, as when we create them, we indicate what type of objects we are going to keep in them. Let’s recall that we create an instance of a generic class, for example GenericType, by indicating the type, of which the elements have to be:

| GenericType<T> instance = new GenericType<T>(); |

This type T can be any successor of the class System.Object, for example string or DateTime. Here are few examples:

| List<int> intList = new List<int>();List<bool> boolList = new List<bool>();List<double> realNumbersList = new List<double>(); |

Let’s consider some of the generic collections in .NET Framework.

List<T> is the generic variant of ArrayList. When we create an object of type List<T>, we indicate the type of the elements, which will be hold in the list, i.e. we substitute the denoted by T type with some real data type (for example number or string).

Let’s consider a case in which we would like to create a list of integer elements. We could do this in the following way:

| List<int> intList = new List<int>(); |

Thus the created list can contain only integer numbers and cannot contain other objects, for example strings. If we try to add to List<int> an object of type string, we are going to get a compilation error. Via the generic types the C# compiler protects us from mistakes when working with collections.

The List Class – Array-Based Implementation

List<T> works like our class CustomArrayList<T>. It keeps its elements in the memory as an array, which is partially in use and partially free for new elements (blank). Thanks to the reserved blank elements in the array, the operation append almost always manages to add the new element without the need to resize the array. Sometimes, of course, the array has to be resized, but as each resize would double the size of the array, resizing happens so seldom that it can be ignored in comparison to the count of append operations. We could imagine a List<T> like an array, which has some capacity and is filled to a certain level:

Thanks to the preliminarily allocated capacity of the array, containing the elements of the class List<T>, it can be extremely efficient data structure when it is necessary to add elements fast, extract elements and access the elements by index. Still, it is pretty slow in inserting and removing elements unless these elements are at the last position.

We could say that List<T> combines the good sides of lists and arrays – fast adding, changeable size and direct access by index.

When to Use List<T>?

We already explained that the List<T> class uses an inner array for keeping the elements and the array doubles its size when it gets overfilled. Such implementation causes the following good and bad sides:

– The search by index is very fast – we can access with equal speed each of the elements, regardless of the count of elements.

– The search for an element by value works with as many comparisons as the count of elements (in the worst case), i.e. it is slow.

– Inserting and removing elements is a slow operation – when we add or remove elements, especially if they are not in the end of the array, we have to shift the rest of the elements and this is a slow operation.

– When adding a new element, sometimes we have to increase the capacity of the array, which is a slow operation, but it happens seldom and the average speed of insertion to List does not depend on the count of elements, i.e. it works very fast.

| Use List<T> when you don’t expect frequent insertion and deletion of elements, but you expect to add new elements at the end of the list or to access the elements by index. |

Prime Numbers in Given Interval – Example

After we got familiar with the implementation of the structure list and the class List<T>, let’s see how to use them. We are going to consider the problem for finding the prime numbers in a certain interval. For this purpose we have to use the following algorithm:

| static List<int> GetPrimes(int start, int end){ List<int> primesList = new List<int>(); for (int num = start; num <= end; num++) { bool prime = true; double numSqrt = Math.Sqrt(num); for (int div = 2; div <= numSqrt; div++) { if (num % div == 0) { prime = false; break; } } if (prime) { primesList.Add(num); } } return primesList;} static void Main(){ List<int> primes = GetPrimes(200, 300); foreach (var item in primes) { Console.Write (“{0} “, item); }} |

From the mathematics we know that if a number is not prime it has at least one divisor in the interval [2 … square root from the given number]. This is what we use in the example above. For each number we look for a divisor in this interval. If we find a divisor, then the number is not prime and we could continue with the next number from the interval. Gradually, by adding the prime numbers we fill the list, after which we traverse it and print it on the screen. Here is how the output of the code above looks like:

| 211 223 227 229 233 239 241 251 257 263 269 271 277 281 283 293 |

Union and Intersection of Lists – Example

Let’s consider a more interesting example – let’s write a program, which can find the union and the intersection of two sets of numbers.

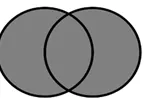

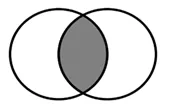

Union Intersection

We could consider that there are two lists of numbers and we would like to take the elements, which are in both sets (intersection), or we look for those elements, which are at least in one of the sets (union).

Let’s discuss one possible solution to the problem:

| static List<int> Union( List<int> firstList, List<int> secondList){ List<int> union = new List<int>(); union.AddRange(firstList); foreach (var item in secondList) { if (!union.Contains(item)) { union.Add(item); } } return union;} static List<int> Intersect(List<int> firstList, List<int> secondList){ List<int> intersect = new List<int>(); foreach (var item in firstList) { if (secondList.Contains(item)) { intersect.Add(item); } } return intersect;} static void PrintList(List<int> list){ Console.Write(“{ “); foreach (var item in list) { Console.Write(item); Console.Write(” “); } Console.WriteLine(“}”);} static void Main(){ List<int> firstList = new List<int>(); firstList.Add(1); firstList.Add(2); firstList.Add(3); firstList.Add(4); firstList.Add(5); Console.Write(“firstList = “); PrintList(firstList); List<int> secondList = new List<int>(); secondList.Add(2); secondList.Add(4); secondList.Add(6); Console.Write(“secondList = “); PrintList(secondList); List<int> unionList = Union(firstList, secondList); Console.Write(“union = “); PrintList(unionList); List<int> intersectList = Intersect(firstList, secondList); Console.Write(“intersect = “); PrintList(intersectList);} |

The program logic in this solution directly follows the definitions of union and intersection of sets. We use the operations for searching for an element in a list and insertion of a new element in a list.

We are going to solve the problem in one more way: by using the method AddRange<T>(IEnumerable<T> collection) from the class List<T>:

| static void Main(){ List<int> firstList = new List<int>(); firstList.Add(1); firstList.Add(2); firstList.Add(3); firstList.Add(4); firstList.Add(5); Console.Write(“firstList = “); PrintList(firstList); List<int> secondList = new List<int>(); secondList.Add(2); secondList.Add(4); secondList.Add(6); Console.Write(“secondList = “); PrintList(secondList); List<int> unionList = new List<int>(); unionList.AddRange(firstList); for (int i = unionList.Count-1; i >= 0; i–) { if (secondList.Contains(unionList[i])) { unionList.RemoveAt(i); } } unionList.AddRange(secondList); Console.Write(“union = “); PrintList(unionList); List<int> intersectList = new List<int>(); intersectList.AddRange(firstList); for (int i = intersectList.Count-1; i >= 0; i–) { if (!secondList.Contains(intersectList[i])) { intersectList.RemoveAt(i); } } Console.Write(“intersect = “); PrintList(intersectList);} |

In order to intersect the sets we do the following: we put all elements from the first list (via AddRange()), after which we remove all elements, which are not in the second list.

The problem can also be solved even in an easier way by using the method RemoveAll(Predicate<T> match), but it is related to using programming constructs, called delegates and lambda expressions, which are considered in the chapter Lambda Expressions and LINQ. The union we make as we add elements from the first list, after which we remove all elements, which are in the second list, and finally we add all elements of the second list.

The result from the two programs is exactly the same:

| firstList = { 1 2 3 4 5 }secondList = { 2 4 6 }union = { 1 2 3 4 5 6 }intersect = { 2 4 } |

Converting a List to Array and Vice Versa

In C# the conversion of a list to an array is easy by using the given method ToArray(). For the opposite operation we could use the constructor of List<T>(System.Array). Let’s see an example, demonstrating their usage:

| static void Main(){ int[] arr = new int[] { 1, 2, 3 }; List<int> list = new List<int>(arr); int[] convertedArray = list.ToArray();} |

The LinkedList<T> Class

This class is a dynamic implementation of a doubly linked list built in .NET Framework. Its elements contain a certain value and a pointer to the previous and the next element. The LinkedList<T> class in .NET works in similar fashion like our class DynamicList<T>.

When Should We Use LinkedList<T>?

We saw that the dynamic and the static implementation have their specifics considering the different operations. With a view to the structure of the linked list, we have to have the following in mind:

– The append operation is very fast, because the list always knows its last element (tail).

– Inserting a new element at a random position in the list is very fast (unlike List<T>) if we have a pointer to this position, e.g. if we insert at the list start or at the list end.

– Searching for elements by index or by value in LinkedList is a slow operation, as we have to scan all elements consecutively by beginning from the start of the list.

– Removing elements is a slow operation, because it includes searching.

Basic Operations in the LinkedList<T> Class

LinkedList<T> has the same operations as in List<T>, which makes the two classes interchangeable, but in fact List<T> is used more often. Later we are going to see that LinkedList<T> is used when working with queues.

When Should We Use LinkedList<T>?

Using LinkedList<T> is preferable when we have to add / remove elements at both ends of the list and when the access to the elements is consequential.

However, when we have to access the elements by index, then List<T> is a more appropriate choice.

Considering memory, LinkedList<T> generally takes more space because it holds the value and several additional pointers for each element. List<T> also takes additional space because it allocates memory for more elements than it actually uses (it keeps bigger capacity than the number of its elements).

Let’s imagine several cubes, which we have put one above other. We could put a new cube on the top, as well as remove the highest cube. Or let’s imagine a chest. In order to take out the clothes on the bottom, first we have to take out the clothes above them.

This is the classical data structure stack – we could add elements on the top and remove the element, which has been added last, but no the previous ones (the ones that are below it). In programming the stack is a commonly used data structure. The stack is used internally by the .NET virtual machine (CLR) for keeping the variables of the program and the parameters of the called methods (it is called program execution stack).

The Abstract Data Type “Stack”

The stack is a data structure, which implements the behavior “last in – first out” (LIFO). As we saw with the cubes, the elements could be added and removed only on the top of the stack.

ADT stack provides 3 major operations: push (add an element at the top of the stack), pop (take the last added element from the top of the stack) and peek (get the element form the top of the stack without removing it).

The data structure stack can also have different implementations, but we are going to consider two – dynamic and static implementation.

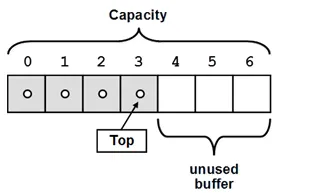

Static Stack (Array-Based Implementation)

Like with the static list we can use an array to keep the elements of the stack. We can keep an index or a pointer to the element, which is at the top.

Usually, if the internal array is filled, we have to resize it (to allocate twice more memory), like this happens with the static list (ArrayList, List<T> and CustomArrayList<T>). Unused buffer memory should be hold to ensure fast push and pop operations.

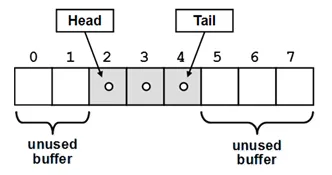

Here is how we could imagine a static stack:

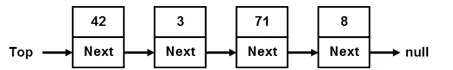

Linked Stack (Dynamic Implementation)

For the dynamic implementation of stack we use elements, which keep a value and a pointer to the next element. This linked-list based implementation does not require an internal buffer, does not need to grow when the buffer is full and has virtually the same performance for the major operations like the static implementation:

When the stack is empty, the top has value null. When a new item is added, it is inserted on a position where the top indicates, after which the top is redirected to the new element. Removal is done by deleting the first element, pointed by the top pointer.

In C# we could use the standard implementation of the class in .NET Framework System.Collections.Generics.Stack<T>. It is implemented statically with an array, as the array is resized when needed.

The Stack<T> Class – Basic Operations

All basic operations for working with a stack are implemented:

– Push(T) – adds a new element on the top of the stack

– Pop() – returns the highest element and removes it from the stack

– Peek() – returns the highest element without removing it

– Count – returns the count of elements in the stack

– Clear() – retrieves all elements from the stack

– Contains(T) – check whether the stack contains the element

– ToArray() – returns an array, containing all elements of the stack

Stack Usage – Example

Let’s take a look at a simple example on how to use stack. We are going to add several elements, after which we are going to print them on the console.

| static void Main(){ Stack<string> stack = new Stack<string>(); stack.Push(“1. John”); stack.Push(“2. Nicolas”); stack.Push(“3. Mary”); stack.Push(“4. George”); Console.WriteLine(“Top = ” + stack.Peek()); while (stack.Count > 0) { string personName = stack.Pop(); Console.WriteLine(personName); }} |

As the stack is a “last in, first out” (LIFO) structure, the program is going to print the records in a reversed order. Here is its output:

| Top = 4. George4. George3. Mary2. Nicolas1. John |

Correct Brackets Check – Example

Let’s consider the following task: we have an expression, in which we would like to check whether the brackets are put correctly. This means to check if the count of the opening brackets is equal to the count of the closing brackets and all opening brackets match their respective closing brackets. The specification of the stack allows us to check whether the bracket we have met has a corresponding closing bracket. When we meet an opening bracket, we add it to the stack. When we meet a closing bracket, we remove an element from the stack. If the stack becomes empty before the end of the program in a moment when we have to remove an element, the brackets are incorrectly placed. The same remains if in the end of the expression there are elements in the stack. Here is a sample implementation:

| static void Main(){ string expression = “1 + (3 + 2 – (2+3)*4 – ((3+1)*(4-2)))”; Stack<int> stack = new Stack<int>(); bool correctBrackets = true; for (int index = 0; index < expression.Length; index++) { char ch = expression[index]; if (ch == ‘(‘) { stack.Push(index); } else if (ch == ‘)’) { if (stack.Count == 0) { correctBrackets = false; break; } stack.Pop(); } } if (stack.Count != 0) { correctBrackets = false; } Console.WriteLine(“Are the brackets correct? ” + correctBrackets);} |

Here is how the output of the sample program looks like:

| Are the brackets correct? True |

Queue

The “queue” data structure is created to model queues, for example a queue of waiting for printing documents, waiting processes to access a common resource, and others. Such queues are very convenient and are naturally modeled via the structure “queue”. In queues we can add elements only on the back and retrieve elements only at the front.

For instance, we would like to buy a ticket for a concert. If we go earlier, we are going to buy earlier a ticket. If we are late, we will have to go at the end of the queue and wait for everyone who has come earlier. This behavior is analogical for the objects in ADT queue.

Abstract Data Type “Queue”

The abstract data structure “queue” satisfies the behavior “first in – first out” (FIFO). Elements added to the queue are appended at the end of the queue, and when elements are extracted, they are taken from the beginning of the queue (in the order they were added). Thus the queue behaves like a list with two ends (head and tail), just like the queues for tickets.

Like with the lists, the ADT queue could be implemented statically (as resizable array) and dynamically (as pointer-based linked list).

Static Queue (Array-Based Implementation)

In the static queue we could use an array for keeping the elements. When adding an element, it is inserted at the index, which follows the end of queue. After that the end points at the newly added element. When removing an element, we take the element, which is pointed by the head of the queue. After that the head starts to point at the next element. Thus the queue moves to the end of the array. When it reaches the end of the array, when adding a new element, it is inserted at the beginning of the array. That is why the implementation is called “looped queue“, as we mentally stick the beginning and the end of the array and the queue orbits it:

Static queue keeps an internal buffer with bigger capacity than the actual number of elements in the queue. Like in the static list implementation, when the space allocated for the queue elements is finished, the internal buffer grows (usually doubles its size).

The major operations in the queue ADT are enqueue (append at the end of the queue) and dequeue (retrieve an element from the start of the queue).

Linked Queue (Dynamic Implementation)

The dynamic implementation of queue ADT looks like the implementation of the linked list. Like in the linked list, the elements consist of two parts – a value and a pointer to the next element:

However, here elements are added at the end of the queue (tail), and are retrieved from its beginning (head), while we have no permission to get or add elements at any another position.

The Queue<T> Class

In C# we use the static implementation of queue via the Queue<T> class. Here we could indicate the type of the elements we are going to work with, as the queue and the linked list are generic types.

The Queue<T> – Basic Operations

Queue<T> class provides the basic operations, specific for the data structure queue. Here are some of the most frequently used:

– Enqueue(T) – inserts an element at the end of the queue

– Dequeue() – retrieves the element from the beginning of the queue and removes it

– Peek() – returns the element from the beginning of the queue without removing it

– Clear() – removes all elements from the queue

– Contains(T) – checks if the queue contains the element

– Count – returns the amount of elements in the queue

Queue Usage – Example

Let’s consider a simple example. Let’s create a queue and add several elements to it. After that we are going to retrieve all elements and print them on the console:

| static void Main(){ Queue<string> queue = new Queue<string>(); queue.Enqueue(“Message One”); queue.Enqueue(“Message Two”); queue.Enqueue(“Message Three”); queue.Enqueue(“Message Four”); while (queue.Count > 0) { string msg = queue.Dequeue(); Console.WriteLine(msg); }} |

Here is how the output of the sample program looks like:

| Message OneMessage TwoMessage ThreeMessage Four |

You can see that the elements leave the queue in the order, in which they have entered the queue. This is because the queue is FIFO structure (first-in, first out).

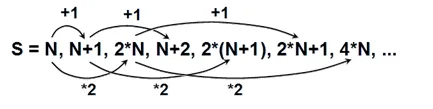

Sequence N, N+1, 2*N – Example

Let’s consider a problem in which the usage of the data structure queue would be very useful for the implementation. Let’s take the sequence of numbers, the elements of which are derived in the following way: the first element is N; the second element is derived by adding 1 to N; the third element – by multiplying the first element by 2 and thus we successively multiply each element by 2 and insert it at the end of the sequence, after which we add 1 to it and insert it at the end of the sequence. We could illustrate the process with the following figure:

As you can see, the process lies in retrieving elements from the beginning of the queue and placing others in its end. Let’s see the sample implementation, in which N=3 and we search for the number of the element with value 16:

| static void Main(){ int n = 3; int p = 16; Queue<int> queue = new Queue<int>(); queue.Enqueue(n); int index = 0; Console.WriteLine(“S =”); while (queue.Count > 0) { index++; int current = queue.Dequeue(); Console.WriteLine(” ” + current); if (current == p) { Console.WriteLine(); Console.WriteLine(“Index = ” + index); return; } queue.Enqueue(current + 1); queue.Enqueue(2 * current); }} |

Here is how the output of the above program looks like:

| S = 3 4 6 5 8 7 12 6 10 9 16Index = 11 |

As you can see, stack and queue are two specific data structures with strictly defined rules for the order of the elements in them. We used queue when we expected to get the elements in the order we inserted them, while we used stack when we needed the elements in reverse order.

1. Write a program that reads from the console a sequence of positive integer numbers. The sequence ends when empty line is entered. Calculate and print the sum and the average of the sequence. Keep the sequence in List<int>.

2. Write a program, which reads from the console N integers and prints them in reversed order. Use the Stack<int> class.

3. Write a program that reads from the console a sequence of positive integer numbers. The sequence ends when an empty line is entered. Print the sequence sorted in ascending order.

4. Write a method that finds the longest subsequence of equal numbers in a given List<int> and returns the result as new List<int>. Write a program to test whether the method works correctly.

5. Write a program, which removes all negative numbers from a sequence.

Example: array = {19, -10, 12, -6, -3, 34, -2, 5} à {19, 12, 34, 5}

6. Write a program that removes from a given sequence all numbers that appear an odd count of times.

Example: array = {4, 2, 2, 5, 2, 3, 2, 3, 1, 5, 2} à {5, 3, 3, 5}

7. Write a program that finds in a given array of integers (in the range [0…1000]) how many times each of them occurs.

Example: array = {3, 4, 4, 2, 3, 3, 4, 3, 2}

2 à 2 times

3 à 4 times

4 à 3 times

8. The majorant of an array of size N is a value that occurs in it at least N/2 + 1 times. Write a program that finds the majorant of given array and prints it. If it does not exist, print “The majorant does not exist!”.

Example: {2, 2, 3, 3, 2, 3, 4, 3, 3} à 3

9. We are given the following sequence:

S1 = N;

S2 = S1 + 1;

S3 = 2*S1 + 1;

S4 = S1 + 2;

S5 = S2 + 1;

S6 = 2*S2 + 1;

S7 = S2 + 2;

…

Using the Queue<T> class, write a program which by given N prints on the console the first 50 elements of the sequence.

Example: N=2 à 2, 3, 5, 4, 4, 7, 5, 6, 11, 7, 5, 9, 6, …

10. We are given N and M and the following operations:

N = N+1

N = N+2

N = N*2

Write a program, which finds the shortest subsequence from the operations, which starts with N and ends with M. Use queue.

Example: N = 5, M = 16

Subsequence: 5 à 7 à 8 à 16

11. Implement the data structure dynamic doubly linked list (DoublyLinkedList<T>) – list, the elements of which have pointers both to the next and the previous elements. Implement the operations for adding, removing and searching for an element, as well as inserting an element at a given index, retrieving an element by a given index and a method, which returns an array with the elements of the list.

12. Create a DynamicStack<T> class to implement dynamically a stack (like a linked list, where each element knows its previous element and the stack knows its last element). Add methods for all commonly used operations like Push(), Pop(), Peek(), Clear() and Count.

13. Implement the data structure “Deque“. This is a specific list-like structure, similar to stack and queue, allowing to add elements at the beginning and at the end of the structure. Implement the operations for adding and removing elements, as well as clearing the deque. If an operation is invalid, throw an appropriate exception.

14. Implement the structure “Circular Queue” with array, which doubles its capacity when its capacity is full. Implement the necessary methods for adding, removing the element in succession and retrieving without removing the element in succession. If an operation is invalid, throw an appropriate exception.

15. Implement numbers sorting in a dynamic linked list without using an additional array or other data structure.

16. Using queue, implement a complete traversal of all directories on your hard disk and print them on the console. Implement the algorithm Breadth-First-Search (BFS) – you may find some articles in the internet.

17. Using queue, implement a complete traversal of all directories on your hard disk and print them on the console. Implement the algorithm Depth-First-Search (DFS) – you may find some articles in the internet.

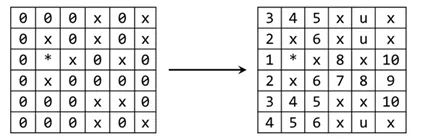

18. We are given a labyrinth of size N x N. Some of the cells of the labyrinth are empty (0), and others are filled (x). We can move from an empty cell to another empty cell, if the cells are separated by a single wall. We are given a start position (*). Calculate and fill the labyrinth as follows: in each empty cell put the minimal distance from the start position to this cell. If some cell cannot be reached, fill it with “u“.

Example:

1. See the section “List<T>“.

2. Use Stack<int>.

3. Keep the numbers in List<T> and finally use its Sort() method.

4. Use List<int>. Scan the list with a for-loop (1 … n-1) while keeping two variables: start and length. Initially start=0, length=1. At each loop iteration if the number at the left is the same as the current number, increase length. Otherwise restart from the current cell (start=current, length=1). Remember the current start and length every time when the current length becomes better than the current maximal length. Finally create a new list and copy the found sequence to it.

Testing could be done through a sequence of examples and comparisons, e.g. {1} à {1}; {1, 2} à {1}; {1, 1} à {1, 1}; {1, 2, 2, 3} à {2, 2}; {1, 2, 2} à {2, 2}; {1, 1, 2} à {1, 1}; {1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3} à {1, 1, 1}; {1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3} à {2, 2, 2, 2}; …

5. Use list. Perform a left-to-right scan through all elements. If the current number is positive, add it to the result, otherwise, skip it.

6. Slow solution: pass through the elements with a for-loop. For each element p count how many times p appears in the list (with a nested for-loop). If it is even number of times, append p to the result list (which is initially empty). Finally print the result list.

* Fast solution: use a hash-table (Dictionary<int, int>). With a single scan calculate count[p] (the number of occurrences of p in the input sequence) for each number p from the input sequence. With another single scan pass though all numbers p and append p to the result only when count[p] is even. Read about hash tables from the chapter “Dictionaries, Hash-Tables and Sets”.

7. Make a new array “occurrences” with size 1001. After that scan through the list and for each number p increment the corresponding value of its occurrences (occurrences[p]++). Thus, at each index, where the value is not 0, we have an occurring number, so we print it.

8. Use list. Sort the list and you are going to get the equal numbers next to one another. Scan the array by counting the number of occurrences of each number. If up to a certain moment a number has occurred N/2+1 times, this is the majorant and there is no need to check further. If after position N/2+1 there is a new number (a majorant is not found until this moment), there is no need to search further – even in the case when the list is filled with the current number to the end, it will not occur N/2+1 times.

Another solution: Use a stack. Scan through the elements. At each step if the element at the top of the stack is different from the next element form the input sequence, remove the element from the stack. Otherwise append the element to the stack. Finally the majorant will be in stack (if it exists). Why? Each time when we find any two different elements, we discard both of them. And this operation keeps the majorant the same and decreases the length of the sequence, right? If we repeat this as much times as possible, finally the stack will hold only elements with the same value – the majorant.

9. Use queue. In the beginning add N to the queue. After that take the current element M and add to the queue M+1, then 2*M + 1 and then M+2. Repeat the same for the next element in a loop. At each step in the loop print M and if at certain point the queue size reaches 50, break the loop and finish the calculation.

10. Use the data structure queue. Firstly, add to the queue N. Repeat the following in a loop until M is reached: remove a number X from the queue and add 3 new elements: X * 2, X + 2 and X + 1. Do not add numbers greater than M. As optimization of the solution, try to avoid repeating numbers in the queue.

11. Implement DoubleLinkedListNode<T> class, which has fields Previous, Next and Value. It will hold to hold a single list node. Implement also DoubleLinkedList<T> class to hold the whole list.

12. Use singly linked list (similar to the list from the previous task, but only with a field Previous, without a field Next).

13. Just modify your implementation of doubly-linked list to enable adding and removing from both its head and tail. Another solution is to use circular buffer (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circular_buffer). When the buffer is full, create a new buffer of double size and move all existing elements to it.

14. Use array. When you reach the last index, you need to add the next element at the beginning of the array. For the correct calculation of the indices use the remainder from the division with the array length. When you need to resize the array, implement it the same way like we implemented the resizing in the “Static List” section.

15. Use the simple Bubble sort. We start with the leftmost element by checking whether it is smaller than the next one. If it is not, we swap their places. Then we compare with the next element and so on and so forth, until we reach a larger element or the end of the array. We return to the start of the array and repeat the same procedure many times until we reach a moment, when we have taken sequentially all elements and no one had to be moved.

16. The algorithm is very easy: we start with an empty queue, in which we put the root directory (from which we start traversing). After that, until the queue is empty, we remove the current directory from the queue, print it on the console and add all its subdirectories to the queue. This way we are going to traverse the entire file system in breadth. If there are no cycles in the file system (as in Windows), the process will be finite.

17. If in the solution of the previous problem we substitute the queue with a stack, we are going to get traversal in depth (DFS).

18. Use Breath-First Search (BFS) by starting from the position, marked with “*“. Each unvisited adjacent to the current cell we fill with the current number + 1. We assume that the value at “*” is 0. After the queue is empty, we traverse the whole matrix and if in some of the cells we have 0, we fill it with “u“.

Comments are closed